Helion | Energy too cheap to meter

Will these innovations usher in an age of energy abundance?

I tried to ask ChatGPT to write a short story of what our world would be like with cheap, abundant energy. Unfortunately, it doesn’t have a great imagination since it’s limited to its training data and it got a bunch of stuff wrong. Thankfully, I didn’t have to look very far to find a real person - a qualified person - who already wrote about that future!

“It is not too much to expect that our children will enjoy in their homes electrical energy too cheap to meter, will know of great periodic regional famines in the world only as matters of history, will travel effortlessly over the seas and under them and through the air with a minimum of danger and at great speeds, and will experience a lifespan far longer than ours, as disease yields and man comes to understand what causes him to age. This is the forecast for an age of peace."

— Former Atomic Energy Commission Chairman Lewis Strauss in 1954

This is a future that we’ve come to know only as science fiction. Energy would never be cheap and abundant, right? How could it? I questioned our ability to find near limitless sources of energy within my lifetime until last December when I read about National Ignition Laboratory’s nuclear fusion breakthrough.

I’ve been wanting to write an article on this topic ever since, but I couldn’t find the right angle. I didn’t just want to cover their breakthrough like a news article. I wanted to do a deep dive into the technology itself which, as you might imagine, was incredibly dense. But after doing my homework, I think you’ll enjoy my take on things.

First, I want to set the scene for fusion since folks tend to have a bad taste in their mouth around anything “nuclear.” But then, I want to dive into one of the most ambitious companies attempting to bring commercial fusion to the masses since that’s really the only way Lewis Strauss’ dream will become a reality. You ready?

Put on your hard hat and let’s dive in.

Welcome to The Glimpse

Join thousands of leaders from companies like Nike, Google, Uber, Coinbase, Twitter and Venmo as we learn how to build the future.

What’s the difference between fusion and fission?

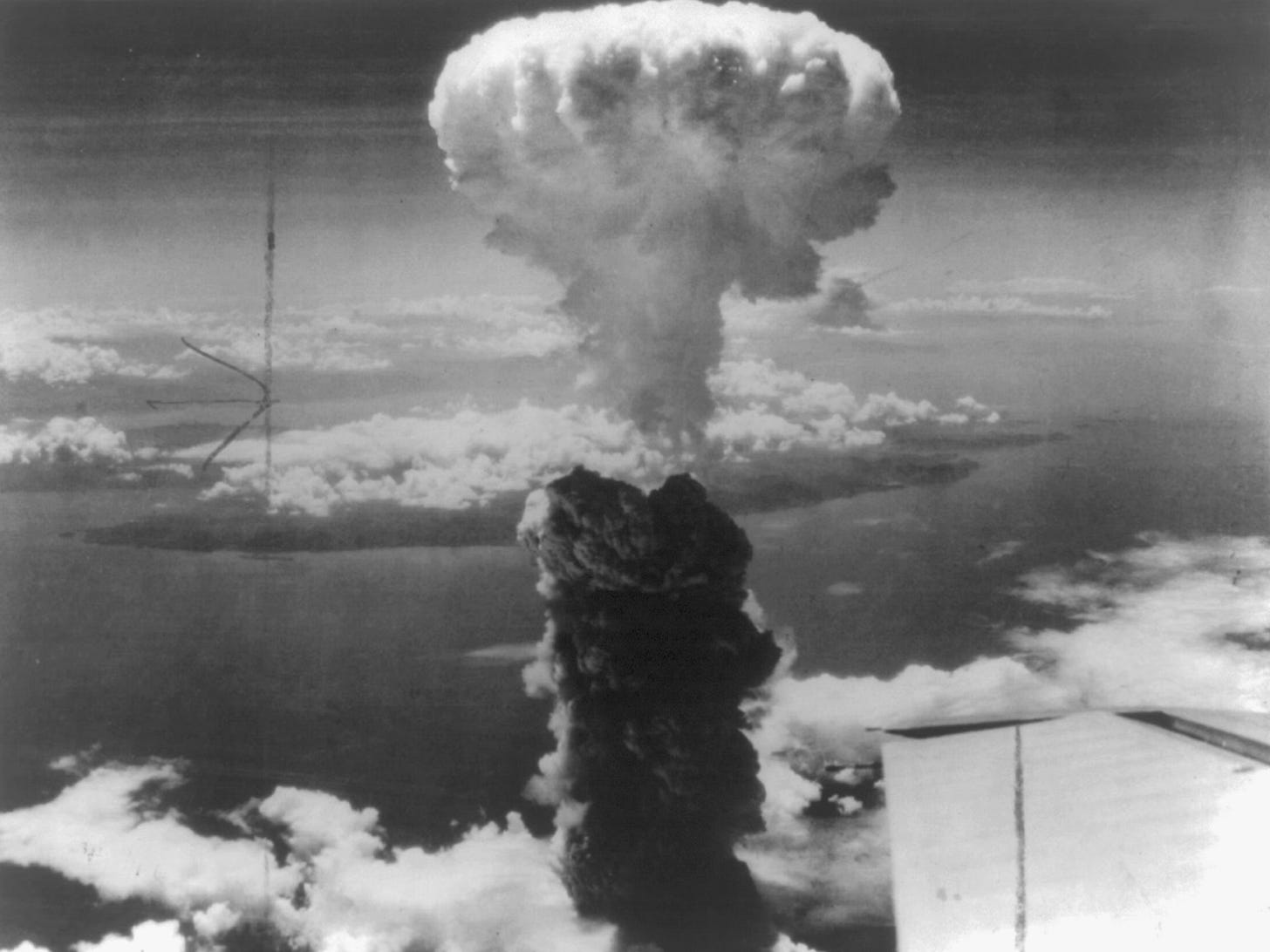

When folks talk about "nuclear energy" they're typically referring to a process called nuclear fission. Fission is the process of firing a neutron into the nucleus of a heavy atom such as Uranium or Plutonium and splitting it into two daughter nuclei. The result is the release of an incredible amount of energy. The first atom bomb used a fission reaction to produce an explosion the equivalent of 20,000 tons of TNT (or 84 Terajoules).

As you might imagine, that scientific breakthrough ignited the imaginations of everyone who dreamed of an energy-abundant future. The energy produced per unit of mass was millions of times more than the energy produced through the traditional combustion of fossil fuels. If we could harness that energy, we would be well on our way to a future where energy was "too cheap to meter."

But of course, the dreams of energy abundance had to be weighed against the risk. After all, the original applications of fission were uncontrolled explosions that decimated the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Controlling that reaction would be challenging at best and devastating at worst as we saw nearly 20 years later in 1986 with the meltdown of the nuclear reactor in Chernobyl, Ukraine.

While nuclear fission was putting a sour taste in people's mouths around "nuclear energy," fission's more complicated sibling - nuclear fusion - was still trying to find its footing. While fission would fire a neutron into an atom in order to split it, fusion would literally fuse two atoms together under extremely high pressure and temperatures exceeding 100 million degrees. When the two atoms fuse together, the mass of the fused atom is less than the combined mass of the two individual atoms pre-fuse which results in a mass deficit that can be captured as energy.

While fission uses expensive fuel like Uranium and Plutonium, fusion could use less expensive hydrogen isotopes like Deuterium, not only bringing down the cost of the raw materials but effectively eliminating the risk from radioactive byproduct. On top of being less expensive and less risky, nuclear fusion produced ~4x more energy than nuclear fission.

I know this sounds too good to be true and you're probably waiting for the other shoe to drop so let me just cut to the chase. Fusion is friggin hard.

You have to inject your reaction chamber with your fusion fuel in gas form, heat it to around 1,000,000 degrees so the electrons are stripped from the nucleus and it forms a plasma. As you're heating your plasma, you need to use some sort of plasma containment method - we'll explore these more in a minute - in order to keep that million-degree plasma from burning a hole through the side of your reactor. Then, you have to compress the plasma while superheating it to 100,000,000 degrees, fusing the atoms together and producing a new set of atoms that you can then use to capture energy.

It's one big engineering problem with thousands of variables that all have to be dialed in to perfection. And even then, it's not guaranteed that you'll achieve the sort of energy output that you need in order to make fusion commercially viable. But while the challenges ahead are daunting, I'm optimistic. As we continue our deep dive, you'll begin to see why.

A Short History of Fusion

In 1946, President Truman signed the Atomic Energy Act that essentially pivoted the Manhattan Project into the Atomic Energy Commission post-WWII. A classified project within the AEC called Project Sherwood incubated 3 different plasma containment designs.

The first was the Stellarator at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, the second was the Toroidal Pinch at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, and the third was the Magnetic Mirror at the Livermore National Laboratory. Each of these designs fall under the umbrella of Magnetic Confinement Fusion which uses magnetic fields to contain the white hot plasma.

There's another type called Inertial Confinement Fusion which uses lasers or ion beams to heat up a pellet of fusion fuel which, when it exploded, would use the outward force of the blast to put intense pressure on the fuel within and compress it enough to fuse the atoms. However, the most common version of plasma confinement continues to use magnetic fields.

Fast forward a decade and, in 1958, Soviet scientists created the Tokamak which uses magnetic fields to confine the plasma in a doughnut-shaped configuration that was more efficient, stable, and scalable. After another 10 years of refinement, the Soviets announced that they finally achieved incredibly high temperatures of around 10 million degrees Celsius. The ability to reach these high temperatures in a steady, controlled environment is an important part of achieving a fusion reaction. After announcing their success, fusion teams around the world all honed in on the Tokamak design.

Despite finally creating a stable environment to contain a fusion reaction 500x bigger than the original atomic bomb, we still hadn't cracked the holy grail of net positive energy production, measured by the Q-factor. The Q-factor is the ratio of the energy output to the energy input. If you have a Q-factor of less than 1, that means the energy produced from the reaction is less than the energy required to create the reaction. A Q-factor greater than one means you have created more energy than you spent, something they call ignition.

In December of 2022, we finally achieved ignition for the first time in history. With a Q-factor of 1.5, National Ignition Laboratory (fitting name) proved that they could create a net energy gain. Interestingly, they did so with Inertial Confinement Fusion (ICF) which is a different method than the traditional Tokamak generators which uses Magnetic Confinement.

The Fusion Race 2.0

While clearly a big step forward, experts have stressed time and time again that achieving a Q-factor above 1 doesn't mean it's ready to scale commercially yet. Q-factor can be measured in two different ways: the scientific Q-factor and the engineering Q-factor. The scientific Q measures the thermal energy produced by the plasma against the thermal energy required to heat up the plasma. It doesn't take into account any of the energy required to run the rest of the machine. It's merely measuring the reaction itself. Q engineering, on the other hand, measures the energy produced by the reaction against ALL of the energy used to create that reaction.

National Ignition Laboratory's Q-factor of 1.5 was a scientific Q-factor meaning it wasn't taking into account all of the energy consumed. There are other milestones that must be reached before we can scale fusion commercially such as our ability to efficiently capture the energy that is produced, our ability to capture meaningful net energy production (typically considered to be a Q-factor of 5 to 10).

But don't get me wrong, despite the challenges ahead NIL's work ignited (sorry, pun definitely intended) a new fire for our work on fusion and there are a few dozen startups, each experimenting with their own ideas to bring commercial-scale fusion to life. And there's one in particular that I'm excited about: Helion.

The Shortcomings of the Tokamak

To feel the full weight of Helion's innovation stack, we have to first understand what they're innovating from. The Tokamak generators have been the gold standard of plasma containment methods since the the Soviets achieved 10,000,000-degree temperatures in the 1960's.

The way those generators work is that the Hydrogen ions - Deuterium and Tritium - are used as fuel and heated to extremely high temperatures. As they fuse, the reaction produces a Helium-3 atom and a high-energy neutron. The energy created by the reaction is captured as heat in the walls of the reactor and used to boil water which creates steam. The steam is used to turn a turbine and generate electricity which can then be captured.

Because the Tritium fuel is extremely rare, the brilliant minds at work have figured out a way to create their own Tritium as part of the fusion reaction. When the rogue neutron strikes a Beryllium lining within the wall of the reactor, it splits the Beryllium into a Tritium and a Helium. The Tritium can then be used in the next reaction. While this is a reasonable solution, the neutron that strikes the Beryllium carries 80% of the energy from the initial reaction which means we use 80% of our newly produced energy just to produce more fuel. And unfortunately, because we'd have to use our entire annual supply of Beryllium to create one Tokamak generator, we're effectively trading one rare element (Tritium) for slightly less rare element (Beryllium).

At the end of the day, Tokamak generators will end up going the way of fission reactors - they're too expensive and won't be able to compete with cheaper forms of energy.

That's where Helion comes in.

Introducing Helion

Helion has made a couple of innovations in regards to their fuel that, together, provide the most encouraging path toward an energy abundant future. It promises a cheaper, safer, more efficient fusion reaction.

1. Cheaper

As we've seen, Tokamak machines become expensive due to the Beryllium necessary to produce more Tritium from the fusion reaction. Not only is the Beryllium expensive on its own, it's also expensive to dispose of. Beryllium contains traces of Uranium which, when struck by the high-energy neutrons, becomes slight radioactive. Eventually, the Beryllium lining must be disposed of which incurs an additional cost.

Some companies, like Helion, have opted for a Deuterium-Helium-3 fuel instead of a Deuterium-Tritium fuel which means they don't have to buy the Tritium (expensive) or produce the Tritium with Beryllium (also expensive).

As we've established, Deuterium is incredibly common - it's found abundantly in sea water. Helium-3, on the other hand, is quite rare much like Tritium. In fact, it's so coveted, it's even been suggested that we mine it from the moon - that's how low our supply on earth is. But unlike Tritium, Helion has found a way to produce Helium-3 affordably. They're able to use a fusion reaction similar to how they produce energy, but to create the Helium-3 fuel by fusing two Deuterium together.

Effectively, Helion has found a way to use only Deuterium as their raw fuel source which is ridiculously cheap and abundant.

2. Safer

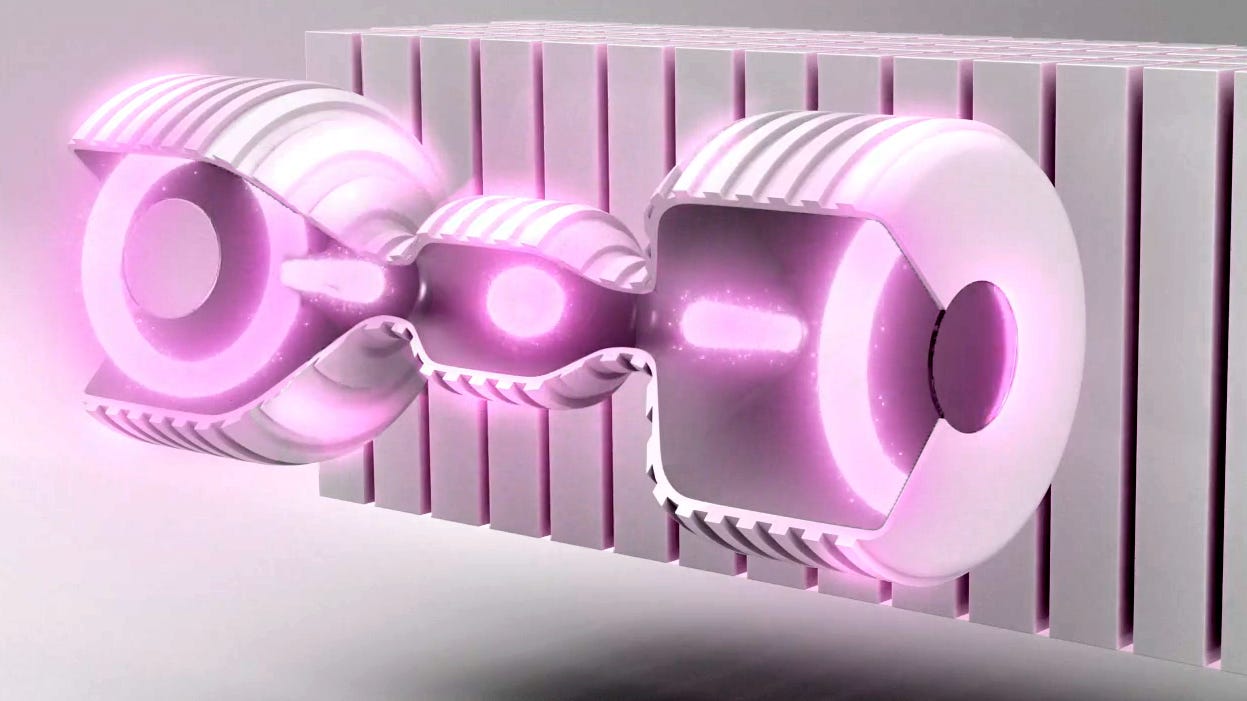

In both traditional Tokamak reactors and Helion's plasma accelerator, magnetic fields are used to contain the 10,000,000-degree plasma. Neutrons, which are non-charged particles, can slip right through and cause damage to your reactor. They're both dangerous and hard to control.

However, because of their unique fuel combination of Deuterium and Helium-3, Helion's fusion reaction is what's called an aneutronic reaction which means it doesn't release a high-energy neutron. Instead it releases a charged particle in the form of a proton which can be safely wrangled by the magnetic field and, as we'll see in a minute, captured directly as energy.

3. More Efficient

Because the Tokamak designs have to translate a non-charged particle (neutron) into electricity, they end up having to take a less efficient approach by boiling water and using steam to turn a turbine. It's quite inefficient and, as one analyst put it,

"If you think this sounds like a complicated and expensive way to boil water, you’re right."

We can look back at the aneutronic reaction that improved the safety of the reactor as our 2-for-1 solution for efficient energy capture as well! Because fusing a Deuterium and a Helium-3 creates energy in the form of a charged proton instead of a non-charged neutron, Helion is able to use that charge to generate energy immediately without having to boil water.

As the magnetic field of the plasma gets stronger, it pushes back against the magnetic field of the machine causing a change in the machine's magnetic flux. That flux change creates a current in the machine's coils which is directly captured as energy.

Interestingly, not only is it more efficient at energy capture, the Deuterium-Helium-3 reaction produces slightly more energy than the Deuterium-Tritium (18.3 MeV) reaction (17.6 MeV). And, per unit mass of fuel, produces ~4x as much energy as a fission reaction.

Conclusion

Despite solving a bunch of lingering problems with the Tokamak generators, Helion's reactor is not without it's share of challenges. Since the Deuterium-Helium-3 fusion reaction requires that it be heated to 100,000,000 degrees, the engineering challenges ahead will not be easy.

Helion is on their 6th generation reactor (called Trenta) today, and are planning to bring their 7th generation reactor (called Polaris) online in 2024. This 8th generation reactor will be the one to prove it can produce electricity. The primary difference between the two will be the level of engineering required as they attempt to run more frequent cycles, ramp up the power output, capture that energy, turn it into 60hz AC, and pipe it back into the electric grid.

Their goal is nothing short of ambitious - a production-ready fusion plant by 2028. Naturally, it's garnered a lot of skepticism from top minds. But whether or not they hit their timelines, I'm excited to see companies running toward fusion with aggressive, startup-level speed. We need a new generation of companies to take the decades of research from academia and government programs to bring nuclear fusion to commercial scale. Soon, there will be a low-cost, abundant fuel that will transform our world in ways we can't imagine.

That's the future that Helion is building.

That’s all for this one - I’ll catch ya next week.

—Jacob ✌️