"Building Product at Wander" with John Andrew Entwistle, CEO of Wander (1/2)

Honest insight on pre-mortems, customer discovery, distribution, flywheels, product development, org design and more from a world-class builder.

You can watch this interview on YouTube, listen to the audio, or read the transcript below.

This interview with John Andrew Entwistle is Part I of a 2-part series on Wander. Part II is a deep dive on Wander’s unique model, exploring their Apple-like playbook to craft a high-end short-term rental experience.

Interview Outline

—— IDEA TO LAUNCH ——

—— BRASS TACKS BUILDING ——

Disclaimer: The interview has been lightly edited for length and readability.

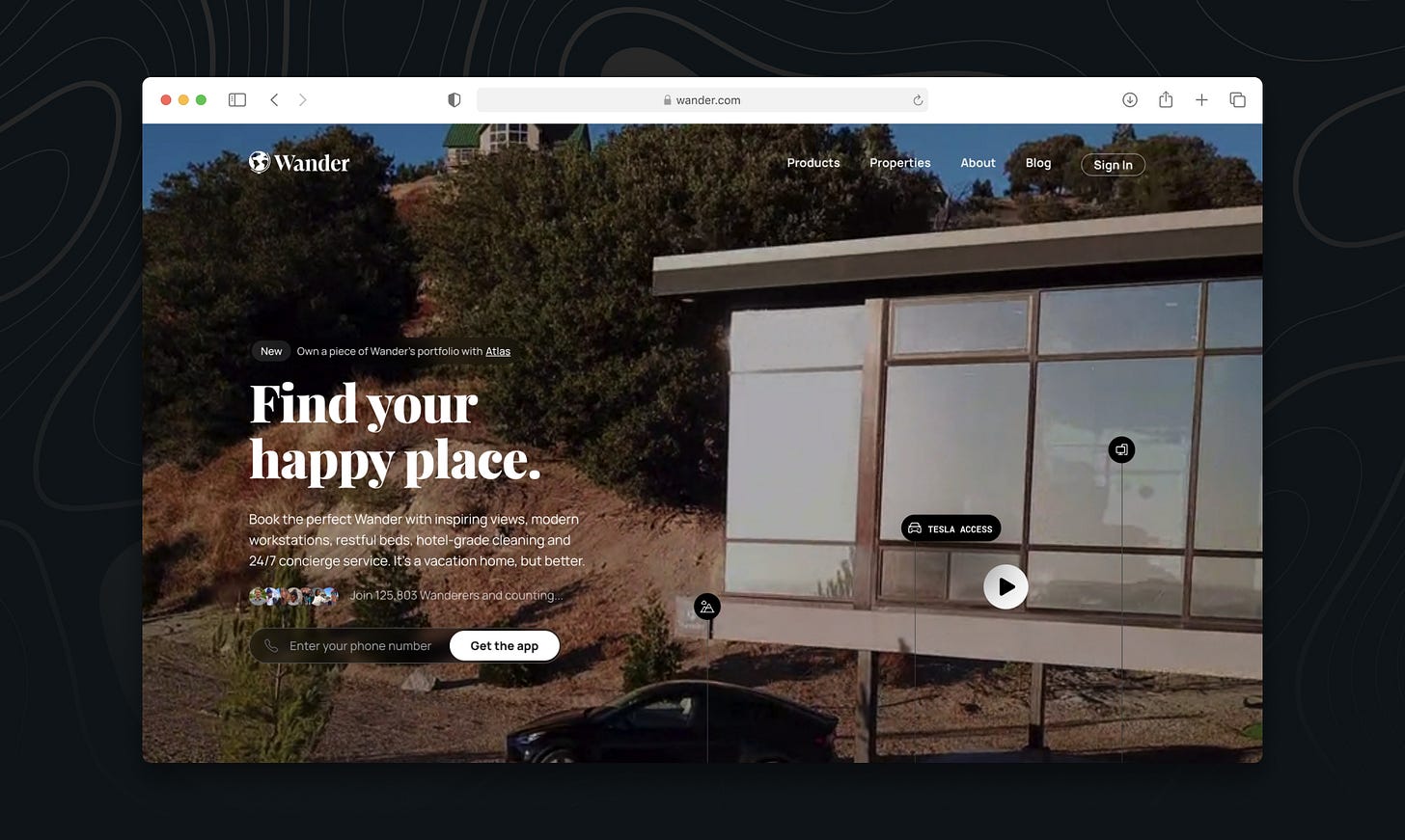

The Wander Experience

Jacob: Let's start with the perfect Wander experience, because I think if you can encapsulate Wander, in one word, it’s about the experience, right?

John Andrew: At the end of the day, it actually doesn't really matter, what my thoughts are on the perfect experience. You're trying to satisfy whatever the desire of the customer is.

And when you think about the different types of people who use Wander, you have people who go on their honeymoon or people who go with their friends, or someone who just needs to go and get away and reflect on a big life change or whatever it may be. So you end up creating this experience that hopefully facilitates all these different types of use cases in as satisfactory of a way as possible for these people.

💡 “Perfect Experience” vs. Standard of Quality

And so what you end up with is this basically standard of quality, right? An example being an iPad, right? An iPad could be used by a musician working on the next big song, or it could be used by a student learning chemistry.

So you have to design this standard of quality for how obviously it's going to be used, and you have no control over what that looks like. And so, for Wander, really what we try and stay to is this idea that every property you visit is going to be absolutely magical. Like it is not going to be your friend's house.

It is it's those types of places on TV and you're like, wow. Like those exist. And then when you get there, the idea is that we want to delight you. We want you to unlock the door with your phone, and then all of a sudden you realize that this is not a normal experience and we want you to see that Tesla in the garage and be like, that's mine? Like I can use that? And then, controlling the temperature of your bed or going and laying out on that daybed, overlooking the ocean and all these different things. And then going a step further, contacting concierge, going and having an incredible dinner, going on an adventure, whatever it looks like. From there, obviously it's up to the user.

We want you to unlock the door with your phone and then all of a sudden you realize that this is not a normal experience. And we want you to see that Tesla in the garage and be like, that's mine? I can use that? And then lay out on that daybed, overlooking the ocean, have an incredible dinner, and go on an adventure.

💡 Designing for Exploration

And one thing that we'll be rolling out soon is this idea of exploration. So when you go to a Wander, you have all these different things around you that pop up on the map from amazing hikes to overlooks to restaurants. Like basically turn it into an Easter egg hunt, and then we're gonna create loyalty around that as well.

So for each thing you go and do you get points and like you build up your level and it turns into this video game of exploring the world in this incredible area that you're in. But I think also, some people won't do that, right? Some people will just sit in bed and drink a coffee and that's also perfectly magical.

It really all depends on the user. And for us, we just focus on the quality of the experience and always trying to delight and then let the user go from there.

Welcome to Making Product Sense

Join thousands of others like you, learning how to build great products and companies from world-class builders.

80-page Pre-mortem

Jacob: You spent a lot of time and a lot of energy putting together an 80-page document, trying to figure out how you would fail, and then trying to come up with solutions for that before you even started.

Can you walk us through that process? How did you come up with ideas that would kill your company, and what did you do in order to find solutions for those ideas?

John Andrew: Starting a company and building a company can be terribly uncomfortable if you like, fuck it up. And even if you don't fuck it up, it's still going to be terribly uncomfortable.

Elon Musk described it as like chewing on glass and staring into the abyss. That's not too far off in terms of the hard times of building your company and so what you want to avoid is starting a company, dedicating your life to it, and then waking up five years later, 10 years later, and all of a sudden like it fails. You accomplished nothing. You learned a lot. But gosh, like 10 years of your life, it's gone. It's incredible how easy that happens.

I'm relatively fortunate that, when I started coder with my co-founders, I was, 17 and that company is still going and successful. But think about how long that was, right? I just turned 25 - it's just amazing how quickly time goes.

You're dedicating yourself at minimum to an 8-year journey to even find out if you failed. Most likely. When you realize that you really want to make sure you're correct on your next idea in your next company, and you find that it's well worth the three months to try and think about the future, think 30 moves ahead, try and kill the idea on paper versus finding out in year four that there was some cataclysmically wrong hypothesis about the market evolution or something along those lines.

You're dedicating yourself at minimum to an 8-year journey to even find out if you failed. So it's well worth the three months to try and think about the future, think 30 moves ahead, try and kill the idea on paper versus finding out in year four that there was some cataclysmically wrong hypothesis about the market evolution.

And so when starting Wander, that was something that I was keenly aware of that I was going to spend as much time as possible thinking about the future, so that when I got to that future, I would hopefully be correct and understand that there would be challenges that would come and we would obviously try and make progress on them. And then that way, all the things that I didn't foresee, at least we'd be in a slightly better position than if I didn't plan at all.

💡 Start With an Executive Summary

When starting that process, which I do for pretty much all ideas, and honestly I should do for like a bunch of the big decisions I make in my life, you start with a simple document and a simple overview of the idea, right? The executive summary, and you write down what it is and why it works and all this sort of stuff.

💡 List Your Questions

And then, the way that I do it, you start asking yourself a bunch of questions and you write them out.

What's the go-to-market strategy?

What does that go-to-market strategy cost?

Why do influencers wanna promote this?

What's my exit strategy?

What is the multiple at IPO that this company is going to have?

And how does that work backwards to a series A?

And the reason it turns into an 80 page document is you end up with six pages of fucking questions and a lot of them are gonna be relatively fuzzy.

💡 Answer Your Questions and Get Organized

But the idea is that you're forcing yourself to think about it and write an answer for each one, and then you organize it into sections, and then it basically turns into something that's relatively readable. It’s super important because it makes you have a level of clarity that most founders don't have. You now have, at least 12 months of clarity and probably three years of additional fuzziness, whereas most founders have two weeks of clarity and maybe a month of fuzzy.

So that's the process that I really recommend.

And I also do the same thing with every new product that Wander launches. So every product that we've launched to date has been defined in that original document. Now I have these new ideas and I see these new adjacencies that I didn't see before, and I run through that same exact process of how does this launch into the next 10 billion dollar business line, and then why does it die? Why does it fail? What's the defensibility?

And so it's a very interesting dynamic as your company grows. But I still think it's really important. Like, you can see the future. I think that's something that most humans don't realize is that like humans can see the future.

You just have to really think about it and you have to basically run scenarios over and over again. And you can create a decent amount of accuracy when you do that. So I think that's the biggest mistake that people make, is they just don't think before they do.

💡 The Trap for Co-Founders

Which I think is also a particularly big trap for companies with multiple co-founders because you come up with an idea, it gets argued for an hour across three people, and then you're like, okay, this is probably correct because, three people went through it. But what you find is that each person only thought about it for an hour, right? So the fact that three people thought about it for an hour means that they all just got an hour deep into the problem. And it would be much better if one person just thought about it for three weeks and then told the other two what they're doing.

Customer Discovery

Jacob: Customer discovery is important for startups from the ground level. They have to understand who their user is and what their user's expectations are.

If we look at it through the "Jobs To Be Done" framework, there's something that they're expecting from their experience that the startup then has to deliver on.

When you consider Wander's "job to be done", how did you go about designing for that? How do you go about finding out what really makes a place feel magical or an experience feel magical?

John Andrew: So first of all, I love how much research you've done into sort of like how we think about the company and those different pillars, so very much appreciate that.

💡 Finding Idea-Market Fit

When it comes down to this idea of how do you define your customer, and then how do you create a product that resonates with them, you have to work backwards from either this idea of idea-market fit or your own intuition, and really you want to combine the two of those concepts.

When you're starting a company and you come up with an idea thesis that you think is correct, you're obviously leveraging your own intuition to start with, right? And that intuition could be very clear if you're your own customer. Everyone inside of Wander is. We're all our own customers. And so we're like, it's relatively clear to us, like what we want, and then whatever we want, we try and think of something that's even higher standard, and we know that's like the minimum that we can do for our customer.

But when you're starting a company, let's say enterprise software, you are not some CIO, you have no idea what they want. You just have a general guess. And so, your next phase is to idea-market fit, which is basically to:

define what that idea is and…

show it to the world and…

look for some type of signal.

And then if there's no signal, you try again.

And if there is signal, you start a bunch of user interviews, you talk to 'em about what they want, and…

then you go and you build that product.

💡 Iterating Toward Perfection

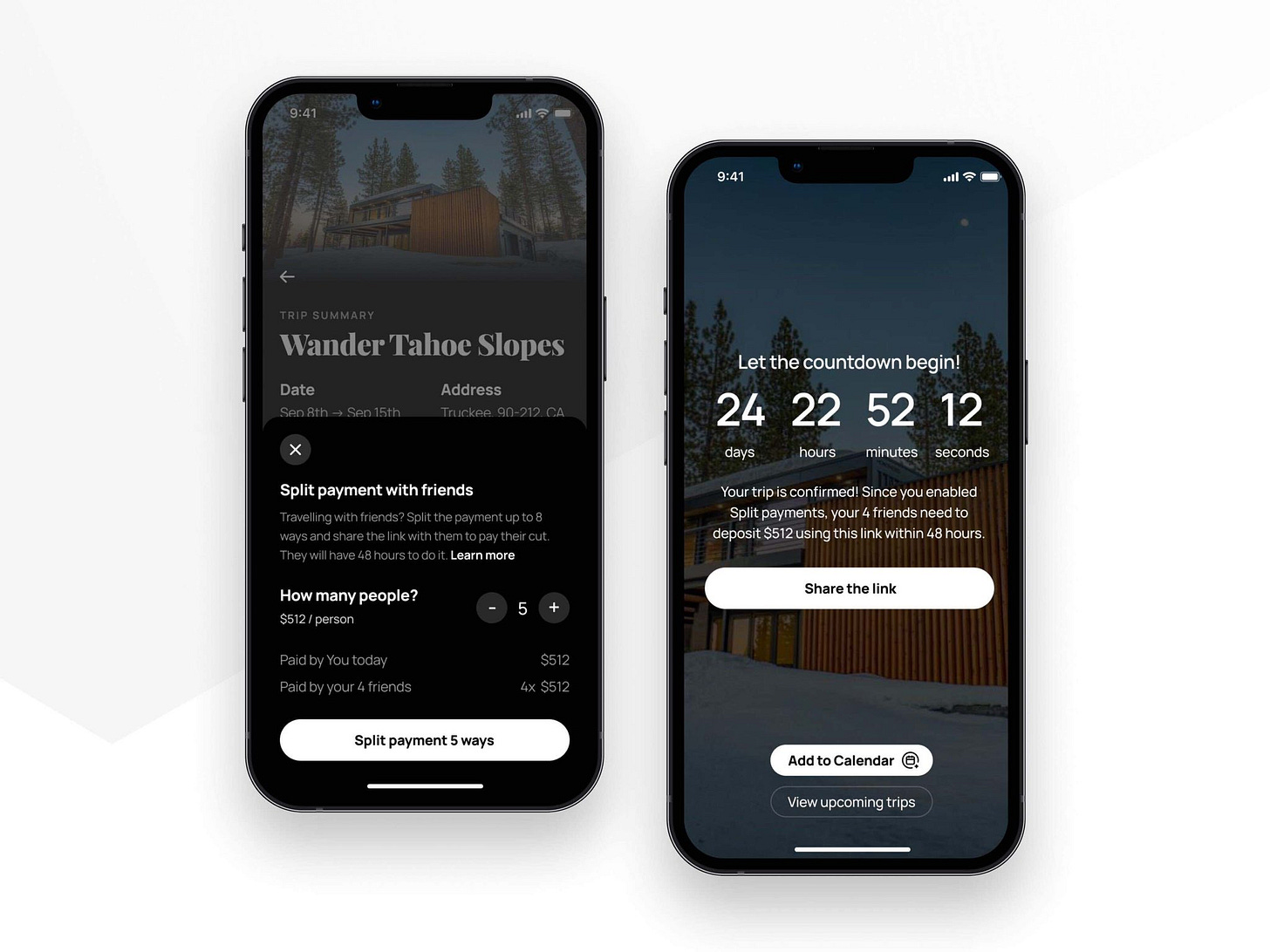

What typically ends up happening in that case as well is that you'll launch that product and you'll have a bunch of signups, but no one's actually going to use your product. And what I look at that as actually a pretty solid success metric because what you have is an idea that people want and an execution that failed. And now you get to obviously iterate towards perfection. Sometimes you get very lucky and you launch the product and everyone just uses it, which candidly, we've been pretty lucky with Wander.

💡 Early Mistakes at Wander

We did make some like mistakes though in the early days, right? When we initially launched, we were very opinionated about the UX .

And we were very opinionated about our operations. So a guest could basically choose a section of time so they could check in on Monday and check out on Wednesday, or they could extend it for a week. That's obviously very company oriented because it makes our operations super easy, right? It means that we have downtime, a hundred percent occupancy, etc.

That is not how like the real world works. No one's like I just happen to want to check in on a Monday and out on Wednesday or out on a Saturday. And so I remember when we launched, we had an incredible first week, I think we generated like $250,000 in revenue or something like it was a pretty, pretty wild week, but, I immediately said like it should have been way more, which I mean in hindsight was also ridiculous mentality. And I went and I contacted every single user and I asked a series of questions like, why didn't you book what happened, etc.

And I graphed those responses in a spreadsheet and it basically was like, they need flexible dates. They want to bring their pet. Like things that are relatively obvious, but when you're opinionated about the user experience or think that a user is more likely to go through something than they are, then you can make those types of mistakes.

And of course, that was fixed two weeks later and off to the races all over again. But I think that's really how you narrow in.

You start with your intuition.

Then you find idea market fit.

You launch that concept (you're likely gonna miss).

You ask everyone why you missed.

You fix those issues.

You look for signal.

I think that when it gets really difficult for companies is when they try and build a product without getting idea market fit first. So you go and you build this whole product. It's super elaborate, it's perfect, but no one even told you they wanted it and you launch it and they're like, yeah, like everything works. I just don't care. I don't actually want this.

Product Distribution

Jacob: How did you get in touch with your initial set of users? Where was your distribution strategy in those early days in order to find out if idea-market fit was even a thing?

John Andrew: Yeah. So there's like a standard set.

💡 Early Stage: Ship, then listen.

The first thing that you do is you throw together a quick website that defines who you are, what you're building, et cetera.

And it can be as simple as like a signup list. And then in terms of sharing that idea what the world, we live in a world where people are hungry for solutions. They're excited to find the next best thing. I mean something as simple as, like, a tweet or a like cheap launch video or otherwise is like all you need. And then from there, obviously you get those initial signups, you can see what people's reaction is to it.

Typically what I recommend is that like before you go and build a huge product, like find idea market fit, and in terms of defining it, just define what your idea is, put it on the internet. No users even need to know that it doesn't exist yet. It can just be a landing page. And that's all the signal you need as a builder.

In the early stages, just wing it, throw up a website, and then get some people to sign up.

💡 Late Stage: Listen, then ship.

For us, we have had it where we launched a product like an idea, especially now a little bit of a later stage company, where the fact that we launched it to see if there was idea market fit before we built it, was actually a negative. And it was a negative because it frustrated users that it wasn't available to them immediately. And then obviously, once we did launch it, then they're like, it's been like, two months. How can I trust you? All these different things.

And so, to summarize the lesson, and this is a lesson I learned rather recently, is that when you have no distribution, just launch everything and see if anyone likes it, and then, yeah, you'll disappoint a hundred people. Not a big deal. But once you have distribution and you're relatively certain, then maybe you should be a little bit more intelligent about your launches so that users can actually consume it when the time comes and you don't end up frustrating this core base of people who are super excited. So it's a little bit of a balance when you get to the later stages.

The Wander Flywheel

Jacob: Was Atlas born out of an answer to one of those pre-mortem questions, or was it a part of the initial vision?

John Andrew: It was born out of an answer.

When you look at real estate, you very quickly realize that finance is the other side of real estate. So you end up looking at capital markets to your debt markets, and then also your equity markets, right? Who's going to own the underlying real estate?

If you do some quick math, let's say with Wander, if Wander has a thousand locations and it has complete control over those locations, and each location is 3 million and you're leveraged at let's say 70%, that's a million dollars of equity per location, that's a billion dollars of equity and 3 billion dollars of debt and like, where the fuck is that gonna come from?

💡 The Wander Flywheel

And so you're like, okay, I could raise a billion dollars of venture capital, provide like a 20% return, and actually it would probably be a decent return for those VCs, but it'd be super dilutive. And so this company's going to need to have dedicated real estate capital. But it also wants to maintain control of the properties and what's the way that you can do this? And also create a flywheel with your consumers where:

More users equals more investors.

More investors equals more properties.

More properties equals more guests.

And you can kickstart that flywheel. Now, that flywheel takes time to start. You need a pretty decent initial base to fully kickstart it. But that's eventually where you can get, and you can blur the lines between customer and owner. And so that was the idea for Atlas. Quick back a napkin math, like where does this money come from, right?

And then is there a consumer opportunity? Is there a flywheel? Is there a way to take this necessity and turn it into an incredible competitive advantage and an incredible moat while unlocking as well, an entirely different business line, right? Because now what you end up seeing is you have this consumer brand that's also this asset manager, which is a business model that's been around for hundreds of years.

If you look at companies like BlackRock and otherwise, then you tie a consumer like brand around it, and then all of a sudden you're like, oh shit. Things are gonna get funky if this is all successful.

It was born out of a question, but honestly, the specificity of Atlas took a lot longer than understanding that we needed to create this vehicle that allowed for ownership. And so I spent probably, at this point, six months, once the company had started, ideating on Atlas and trying to figure out the correct way to do it, and then once we had narrowed in as far down as we could, then we executed.

But yeah it, a lot of your product opportunities will come from questions and that's how you end up building a great ecosystem.

Product Development

Jacob: As far as feature development, how do you take a feature from the idea stage - it's on the roadmap - to executing and launching a feature.

John Andrew: We don't allow for goals to be set more than one month into the future because I don't want the team thinking about or being distracted by or, actually more realistically, allowing for this idea to delay something that's important, which I think a lot of teams do. They're like, we're gonna do this and it's gonna take us two months.

💡 The Icebox

What I'd much rather see is we're going to do this and we're gonna do a small part of it this month, and that's what we're gonna put on The Progress Tracker. But the ideas themselves actually start in what we call The Icebox, which is this grand list of basically all the things that we want to do across the company that is called The Icebox for a reason, because we're busy and like we'll pull things out of it occasionally as a source for the Progress Tracker and work the goals backwards from there.

💡 Roadmapping

So that's where it starts.

It starts with the idea.

That idea gets broken down into steps.

Those steps get prioritized for the current month into related goals.

So it's a relatively simple process, but I think the thing that's interesting is that we break it down immediately, and then the thing that we're focused on is that subset of requirements for that month versus allowing ourselves to drift into this idea of okay, we have three months to complete this whole thing. Because what ends up happening is that you delay everything until month three, and then you miss your deadline. So we break it up into small goals, assign micro deadlines to that and then go from there. And those deadlines for us run on a monthly cadence.

Goal Setting & Planning

Jacob: How do you set goals and plan as a team?

John Andrew: Yeah, so first of all, I hate OKRs. Which the team makes fun of me for, because as our goal setting continues to advance, it starts to have little bits and bobs of OKRs. And I'm like, I don't care if what this evolves into looks exactly like OKRs, I refuse to call it that. We'll call it something else.

💡 The Progress Tracker

When we started the company I created this spreadsheet called the Progress Tracker, which basically was broken up by months and then each month had the related goals and the person who is responsible next to it. Super simple, keeps track of everything, allows me as a solo founder to go in, see everything that's going on as a company and any other employee to go and see everything that's going on as a company.

When we started the Progress Tracker, I think the first month had six goals and they were like… cute. Now, I think last month was 400 goals across the company with various people assigned to them in various departments, and all are evolving and it's available for the whole company to see and anyone can edit it. It takes about three hours for me to go through and understand exactly what's going on and what's the progress and what's at risk and who's responsible for what.

It started out simple. Now that sheet is relatively complex. I'm sure there are many softwares that you could point to that do the exact same thing but I find most productivity software just competes with a well-formatted sheet.

I find it incredibly useful because, even though it does take three hours going through with the leadership team once a week to discuss everything across the company, how many CEOs can say that they know what's going on across the entire company. And how many leadership teams can say that they know what's going on across the entire company at our scale, and how many employees can say that they know literally what the entire company is doing?

💡 Assigning Tasks and Setting Goals

Jacob: And how do you go about the goal setting itself? You've got 400 goals. Who arrives at those goals and sets those for team members?

John Andrew: First of all, as a leader, you have to be coming up with your own goals. And those goals ideally are being tied back to what we call company goals, right? So these are the company goals that we want to achieve this year. And every goal needs to tie back to a company goal in some way, shape, or form to keep the team relatively focused.

So the first thing that happens is I'll set the goals that I have for each department. The things that I know that I want to have them do. Each employee in the company goes and sets their own goals as well, whether it's for them or for other departments, which I think is very critical.

Let's say an engineer needs something from design, like they will go and list that goal so that it can end up being discussed and prioritized. That'll end up being reviewed by the leaders within these departments, consolidated, organized, and then I will go through it with them, make sure that everything's aligned, and ask questions.

Why do we need to do this?

How does this affect this?

Are there too many goals you're gonna end up missing?

And then they get basically set in stone. And once they're set in stone for that month, they're now immutable. So you can cross goals out if they're bad, right? If something changes on the fly and you'll never see it again. But other than that, it's an immutable list and you're responsible for getting it done.

Organizational Design

Jacob: So you have three different products:

Your guest experience,

your Wander platform,

and your financial product, Atlas.

How do you manage such different products across such a broad spectrum of industries? Finance is very different from software and real estate. How do you make sure that you're getting all the information that you need to make educated decisions as a CEO?

John Andrew: It's interesting… the first answer that you come to when you think about that question is this idea of hiring three product managers or three product owners. I actually think that it's a complete fallacy that you need one person for every role.

💡 Traditional Org Charts are Broken

And it's something that I found incredibly fascinating. You think about, let's say, an org chart. In an org chart, it's this two-dimensional idea that shows basically who rolls up into who, and then they have their title and that's like what they own. And what you end up with is a company that's expanding and growing into all these different ideas that thinks that we need one person for every single job, which is completely broken. And it's also, something that every single startup founder recognizes intuitively is, this idea that like I'm only one person, there are 18 jobs to be done, so clearly I'm going to do all of them. It doesn't matter.

And then, for some reason, as you grow and you hire people, you're like, okay this engineer is just an engineer and that's all they can do, when you yourself are doing 18 different jobs. That idea was something that perplexed me to the point where I bought every single book I could find on organizational design, and like organizational psychology because I'm like, this is so broken. It doesn't scale.

💡 The Organizational Graph

I found this idea, which I loved, called the organizational graph, where effectively it shows how a person can have multiple jobs and different jobs can have different reports, in terms of who owns what. And what you end up creating is this idea that's more reflective of people's ability, where that engineer is an incredible front-end engineer, but by the way, they have a journalism major and they wanna review your press releases too.

That's more reflective of a dynamic organization that takes advantage of people's strengths and weaknesses and candidly makes it more exciting for the employee because they get to work on all these different things while obviously continuing to execute on where they're most valuable.

I found this idea called the organizational graph, where a person can have multiple jobs and different jobs can have different reports. That's more reflective of a dynamic organization that takes advantage of people's strengths and weaknesses and makes it more exciting for the employee because they get to work on all these different things while continuing to execute where they're most valuable.

If you look at my my background, it's very much a generalist and company builder, but you also have a lot of experience in marketing and sales and all these different pieces.

And there's things that aren't on my resume. I spent three months building an introductory brokerage, like a Robinhood competitor, for fun. I have a weird knowledge of these financial products and the right UX. And so what you end up creating is this organizational graph that's reflective of all the jobs to be done.

And that's how you end up developing and maintaining high quality products across multiple different ideas. And the thing that unites them all is the fact that they are all related and all intertwine into this ecosystem. When you realize that a company is just a group of people and what they create, the products, is a reflection of them.

Now, how does that scale when you have a million people? I have no idea, but I do know that as an early stage startup, you end up needing to create this web of responsibility to deliver a product that talks to one another.

The Role of Design

Jacob: What is the role of design in Wander? How do you make sure that design doesn't fall through the cracks and it instead becomes a first class citizen of everything that you?

John Andrew: Design goes back to idea-market fit, right? First you make sure that you like the idea and then you need to prove that. And like, in a product it's all visual, it's look and feel. And so for us, because that's what the user interacts with, that is by definition the most important piece. Like I couldn't care less, and I don't mean this in a negative way, about like the quality of the code, if it's not a product that a user wants to use or can use.

By definition, design has to start first because that's what the user interacts with. In terms of creating incredible design, at the end of the day, there's really two different pieces of that.

💡 Part I: Hiring World-class Designers

The first piece is that you need an incredible designer who is aligned with you, your styles, and what you believe is correct or incorrect. You have to be opinionated as a founder. It's like that meme video that's going around where he's talking about like he gets paid for his taste. And everyone makes fun of that. But candidly, like it is very important.

There have been a number of times where a design is about to be shipped. That candidly, I just don't think is good. And I will stop the train. Like I'll just hit the brakes. And everyone also realized it, it's just like they have everything else going on, they weren't thinking about it, etc. And they'll go back to the drawing board with it.

So step number one is having an incredible designer. And I can say at Wander, like everything that we do is thanks to that principle. Michał who's our who's our designer is just absolutely amazing, like a total work horse. Incredible person. I love him to death.

💡 Part II: Maintaining High Standards

The second thing is, like I said, being opinionated and not letting something that's bad ship, because at the end of the day, everyone's on the same team and no one wants that to happen.

Now you want to do so without it turning into like Congress where you have 500 people voting on a design. If you run into issues with your designer constantly, you just need to work with a different designer. You know, it can feel relatively seamless if the designer and you are aligned from a style perspective.

And then maybe you can have one other person. Maybe. Maybe. Most cultures, the designer posts the design in some big chat and everyone gives their opinion. We don't do that at Wander. The designer designs it. I mean at this point I wouldn't even check off on most things. I just assume that it's gonna be great. And if I happen to see a Figma fly by with an issue, it'll get flagged. And that's that.

Limiting the number of stakeholders is very important. And then trusting your designer. And if you can't trust your designer, then you need a different designer.

The Future of Wander

Jacob: We're gonna wrap up with looking forward to the future for Wander.

Is Vacation Rentals a wedge into a broader travel / real estate market? And, as a follow on to that, do you plan to expand beyond homes into workplaces or experiences that are not necessarily homes?

John Andrew: [long pause 😂]

Yes.

You're absolutely correct.

💡 Picking Your Wedge

When you're picking your entry market, you want to create something:

that can create excitement…

that can generate revenue…

that is an emerging asset category…

…so that you have the wind at your back while you're creating. All these different pieces are super critical, and then you obviously want to create differentiation within it.

💡 Finding Your “Idea Space”

What ends up happening is you start to realize what idea space a company is building in and what are the adjacent opportunities that it can expand into without it seeming off.

And when you think about that for Wander, all of a sudden, like it gets really weird really quickly because you can spend maybe 15 minutes thinking about where is this company gonna go? What can it build over the next decade? And you realize that it goes beyond vacation rentals. It can even go beyond experiences that are just limited to ones that we own and manage.

You look at expansion into curated opportunities. You look at expansion into all these different pieces, and you look at the productization of what we've built internally to operate our business.

So the short answer is that in order to see that, you need to think about the idea space, and then you need to think about the mission of the company. And when you do that, then you realize that there's no rules in terms of how it gets there or how big it can be.

And all of a sudden it gets for certain companies, the right types of companies, it gets really exciting, especially ones that have boundless ambition, and that's the type of company we are.

We want to become an important company. Like we want to expand into everything. Which I think is probably a scary statement for anyone who's sees Wander as a competitor, which like, don't be looking at us, like build your own thing, etc. But like we, we want to create the most magical ecosystem for users that touches every single piece of travel and is expansive. And we want to expand our customer set as well, not just to the traveler, but the entire ecosystem that lives around them.

So it'll be a, it'll be a fun, a fun journey. We're definitely not gonna die from lack of opportunity. That's for sure.

What about AirBnB or other competitors?

Jacob: I'm sure you saw this question coming, but there are competitors in this space, the biggest and most well known being Airbnb and their premium offerings or their experience offerings.

How do you see you two co-existing and or are you not gonna coexist and you're going right after them?

John Andrew: I'm trying to think about the answer to this that doesn't get me… I wanna be candid, but I wanna do so in the correct way.

What I can say is that Wander wants to make a product that users want to use, period.

We want to build an experience and an ecosystem that users want to use above anything else, and not because we want to do so to beat a competitor. We want to do so because we want to make our users lives better. I think that if we continue to focus on the customer and the quality and remember that like they are human beings with like feelings and emotions and like all that sort of stuff, and we don't lose that humanity, that with the right strategy and the right team we could end up in an opportunity where we end up creating that platform where over the next 10 years we create a platform that users want to use.

But we'll see. That's easier said than said, than done. And I have tremendous respect for every other company in the space because I recognize that companies are, again, just groups of people. And those people are incredibly talented. They've gone through their own challenges and like at the end of the day, if we're all focused on the customer, it's going to be incredible for the customer. And regardless of what happens, we'll have moved this part of the world forward.

I hope you guys have enjoyed this interview as much as I did. The world is full of hard problems to be solved, and it takes special founders like John Andrew to come up with the unique solutions required. If you enjoyed it, please share it so others can learn from world-class builders.

Subscribe to get Part II, my deep dive into the idea and business of Wander, and more content like this in your inbox next Tuesday!

—Jacob ✌️

❤️ Smash that heart!

If you enjoyed this article, smash that heart icon to show some love! 🙏